Skepta

Here now

It’s fun spending time with Skepta, the British music megastar. He’s always completely in the moment and effortlessly multitasking his way through the day. After making his name in London’s grime scene, the MC has grown where many have fallen by the wayside. He’s now the most celebrated face in British rap culture, with more awards than he can keep track of. The man also known as Joseph Olaitan Adenuga Jr. is many things: a north London legend; a Nigerian chieftain; a figurehead who consistently keeps people on their toes, both sonically and through his adventures in filmmaking, fashion design and more. He’s inspiring. He’s beautiful. He’s got no idea what he’s doing tomorrow. Life’s more exciting that way, after all.

From Fantastic Man n° 41 — 2025

Text by JASON OKUNDAYE

Photography by OLIVER HADLEE PEARCH

Styling by GERRY O’KANE

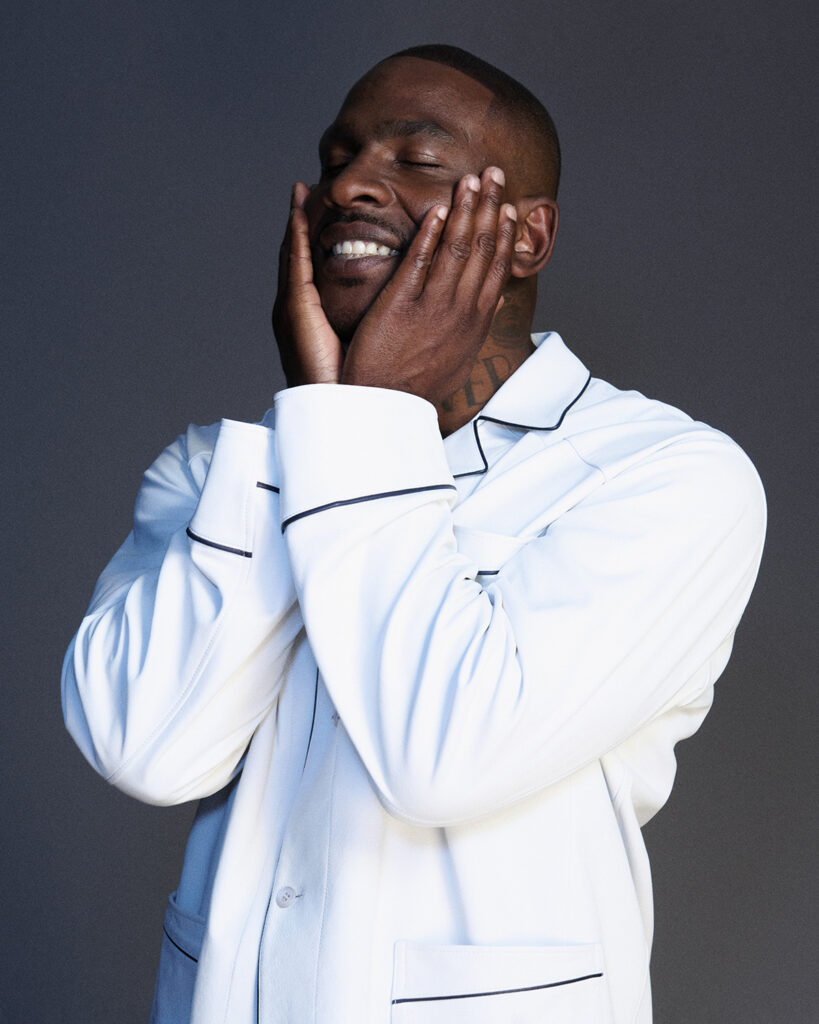

Skepta’s brain is glitching: he puts his hands on his head and shoots bemused looks all over the room, as if searching for something he’s lost. It’s a Tuesday, and we’ve just wrapped up speaking in his studio space in Soho, London, when I ask him if he’s looking forward to his DJ set at the Glade stage of Glastonbury Festival on Friday, where he’s scheduled for a B2B set with Brazilian DJ Mochakk and Turkish DJ Carlita. “When is it, this Friday?” He’s exerted an unruffled calm in the time we’ve spent together, but now a look of panic cloaks his face. His publicist, Kiki, reminds him that it’s an 11pm set. “So, are you looking forward to it?” I ask again. “Yes… I am scared now. It’s crazy when people ask me ‘Should we meet up on Saturday?’ and it’s Tuesday today; I’ll freeze. If someone says something too far away, I’m done.” I’m similarly scatterbrained, so I advise making good use of the iPhone calendar app. This flusters him too; he can never seem to calibrate it on his own device.

Occasional overwhelm and malfunction is an inevitable consequence of being a restless person. As the grime MC and producer tells me, he doesn’t like to have an “idle” mind. You can glean that from his myriad creative pursuits: there is always some kind of mysterious new side mission that Skepta is pursuing. His music of course. But then there’s running his fashion label, MAINS, auctioning off painted works for £81,900 through Sotheby’s, organising a multi-genre music festival (Big Smoke), directing a short film (‘Tribal Mark’), designing sneakers with Puma, getting a chieftaincy in Ogun State, Nigeria, and figure-heading his Más Tiempo record label, focused on house and techno music, which has residencies in Ibiza.

In fact, he’s just returned from this year’s residency, landing back in London from Spain last night. Ibiza was once a space he would use for respite and the typical holiday vices after a long tour, but it is now as much a location for business as for a great time. When he launched Más Tiempo in 2022, he says that reactions were sceptical. It was treated almost as a contradiction for a grime rapper to launch a house-techno project: people thought he was “just trying to finesse the house scene” for more money to add to the pile.

But his education in dance music dates back to the same time as his early underground grime clashes and stints on pirate radio. “It comes from Matt ‘Jam’ Lamont. It comes from EZ. It comes from Todd Edwards. It comes from all those speed-garage tape packs I used to listen to back in the day, those house CDs I used to listen to when I was growing up,” he explains. “Grime is derivative of all those sounds, innit? It’s funny, though, because I know a lot of people are still, like, ‘Hmm…but you’re a rapper,’” he squeezes his face, as if mocking their ignorance, “but then when they get to the set, they’re, like, ‘Wow.’” He explains that this is due to much of the British rap scene’s roots in rave culture. Where Americans might have had their early exposure to entertainment in attending, say, a Lil Wayne concert, for Brits “our school partying is in raves; I’m raving as a teenager, so I’ve had all this time as a raver, then we rap. So it’s, like, now I want to do house music. It’s very second nature to me, so it makes me laugh when people are surprised.”

(THE MAINS STUDIO)

In his studio space, Skepta stands before me topless, wearing only a fitted cap and a pair of denim shorts. They are from his MAINS collection, and he is busy checking their fit and construction. He doesn’t seem too happy with the waist and snatch of the shorts. “Want a bit more of a sexy fit,” he says.

His stylist, Zahra, tells him, “They are sexy.”

“They’re not though. Is it because they’re not my size?” he says.

“You don’t want them to be too baggy.”

“I don’t want them too baggy… That’s what I’m saying!”

“You want them tighter?”

“A tiny bit, Zahra… Like an inchy-wally.”

“What, so you look like you have a BBL [Brazilian Butt Lift]?”

“Not a BBL, allow that bro. Just a tiny bit sexier. Or maybe they’re just not my size.”

There are three levels to Skepta’s headquarters in Soho: on the top floor is his MAINS studio, below that is the recording studio, and below that is the gym. “This building is good for me, because when I’m bored doing music I can come up here and look at some clothes for a while so I’m not always doing the same thing.” The gym, though, is effectively out of action: it is filled to the roof with boxes, effectively a storage space. In the MAINS studio they’re currently preparing their upcoming collection for a Paris showroom, and will also be exhibiting it at London Fashion Week in September – they’re working three months ahead of schedule. He is so engrossed in this that, while he does acknowledge me with a casual fist bump when I enter, he has to be informed of why I’m there, if the publication I’m writing for is any good, and what exactly I want from him. He likes to talk and work at the same time – it “helps things flow” – so while he’s examining himself in the mirror, consulting with head designer, Mikey Pearce, and checking in with his seamstress, Yan, I fire questions at him.

What becomes apparent in the hours we spend together is that Skepta has an intense level of focus, but his surroundings dictate what he wants to talk and think about. Here, we are surrounded by clothes and fabrics, and so the whirring of the sewing machine needle and the scraping of hangers as he rummages through denim jackets and furry ensembles on the rail soundtrack our conversation.

His previous MAINS collection was a rumination on “how we found our swag, so to speak, going to garage raves back in the day and seeing how everybody was dressed.” He used to stand outside of rave venues unable to afford the attire of the glamorous attendees but imagining and falling in love with the fashion; his show this September will be more of an explicit love letter to that raving culture. It’s difficult to imagine Skepta, emblematic of London’s urban influence and taste-making, as sitting on the periphery of swag – on the outside looking in. But he couldn’t get into these raves as a late teenager, for one thing because of his age, but largely because he “never had the money to get the Moschino two-piece and the Patrick Cox loafers. I was wearing my dad’s shoes and some church trousers and a shirt, because that’s all I could afford. I would be looking at the queue and just having the aspiration of wanting to get money, get the clothes, get in the club and dance to DJ EZ.”

Skepta has clearly more than surpassed his aspirations, and he’s undergone transitions in his relationship with fashion. Where grime music had typically harboured an aspirational fascination with luxury, Skepta subverted this on his 2016 track ‘That’s Not Me’, rapping, “Yeah, I used to wear Gucci / I put it all in the bin ’cause that’s not me.”

It’s lyrical bravado, sure, but for Skepta it was less about literally throwing his designers in the trash and more about recognising that fashion now chases street style rather than street style chasing fashion. That is an inversion which has emerged as labels like Louis Vuitton and Dior began to recruit streetwear designs – hoodies and tracksuits, chunky jewellery and loud monogram prints. Skepta now finds himself front row at fashion shows and has starred in campaigns for the likes of Bottega Veneta and Burberry. “Street style is recognised,” he says, “and I feel like that’s all I wanted, because I felt short-changed before.”

(THE RECORDING STUDIO)

We head down a narrow staircase to Skepta’s recording studio. Mercifully without the cascade of boxes and clutter, it is a clean, black room with red accents. He offers me slices of watermelon and mango and a cup of tea. This is where he is still working on his sixth studio album, initially known as ‘Knife and Fork’, then as ‘Fork and Knife’; it has been teased since at least early 2024. I ask for an ETA but am told that any estimation would be a shot in the dark and embarrass the both of us. First, however, we can expect an EP with producer Fred Again. A week before we meet, the two released ‘Victory Lap’, a 140BPM electronic blitzkrieg with a sample of stateside rapper Doechii’s ‘Swamp Bitches’. Skepta can’t remember exactly how this working relationship with Fred came about, but he does say that Fred is someone who “takes me out of my comfort zone… He’s about his music; he’s someone that just loves it. And he keeps coming up with all these crazy ideas.”

But I still want to know about the forthcoming album. What I do know is that it conceptually tracks his parents’ migration from Lagos, Nigeria, to London and the cultural transitions that involves. “I can’t say the whole album is about that,” Skepta says. “There’s a few tracks on there about that. But mostly, I feel like the Skepta on this album is the Skepta that I feel like I should have always been. I feel like the years of me screaming down the microphone and doing interviews and living my life how I’ve wanted it to be have allowed me to now make the album that I want to make.”

I resist an eye roll. That kind of sentimental cliché often comes from artists who have experienced a creative nadir or commercial flop and decided that none of their previous efforts were the “real” them. Skepta’s 2016 and 2019 LPs, ‘Konnichiwa’ and ‘Ignorance Is Bliss’, received critical acclaim; surely he hasn’t run out of things to say?

“What does that mean?” I ask him.

“Because, you know, you’re restricted by space, you’re restricted by fame, you’re restricted by money,” he replies. “You’re restricted by a lot of different factors when you’re coming up in music – you’re even restricted by the brainwash of who you think you’re supposed to be as well, so there’s, like, a facade. You can’t get past the facade boundary. But now that I’m older, I can see the world for what it is. Now I can just be the Skepta that I know that I should be, that I should have been the whole time.”

“But what does this actually mean existentially? Who are you? Who is Joseph Adenuga Junior?”

He sits in quiet introspection for a moment and eats a slice of watermelon. “I am a British immigrant. That’s who I am. I’m somebody who’s too Black to be British, and too English to be a Nigerian. I tread that thin line where it’s like I’m the translator between two things. It’s the reason I can make a banger with Portable [the Nigerian singer he collaborated with on the track ‘Tony Montana’] and I can make a smash with Fred Again.”

Weirdly, it was a conversation with Ed Sheeran that first made him reach this place of self-realisation. In 2013 the two appeared on SB.TV, the grime and hip hop focused YouTube channel run by the late music mogul and entrepreneur Jamal Edwards. Sheeran, who received much of his earliest airplay on SB.TV with a series of (questionable) acoustic-guitar rap tracks and who credits Edwards with having launched his career, had stormed the mainstream with his debut album ‘+’ and was on the cusp of releasing ‘x’, which would propel him to true international superstardom.

“We were waiting outside for our cars to come. At the time I was doing some tracks, and I was saying stuff about these record label execs. And Ed said to me, ‘You know when you talk about what’s-his-name…do you not like him? Do you think he’s shit? Or is it just banter?’ I was, like, ‘No man, I’m just playing with him.’ He’s, like, “Oh, cool, because I just want to know who to go with, innit. I know I’m gonna be big. I’ve got ginger hair. I play guitar and I can sing.’” He was so struck by Sheeran’s self-belief that he froze. “It’s, like, how have you said that so confidently? You’ve put your attributes together and said ‘I know that I’m gonna be big…’ I remember that was one of the moments in my life where I realised, ‘Okay, cool, you just have to choose it.’ You don’t ask whether you’re going to be big. You just choose your attributes and say ‘I’m Nigerian, an immigrant from London. I’ve got this accent. I do grime. And I’m gonna be big.’”

(TOTTENHAM, LONDON)

It is best to reach back to understand how Adenuga became the big man. Skepta grew up on the Meridian Estate in Tottenham with his parents, Joseph Sr. and Ify Adenuga, and his siblings Jamie (rapper JME), Julie and Jason. His father was a DJ who played sets of afrobeat, dancehall, reggae and ska under the name Joe 90 at the Truman Brewery venue in Brick Lane, east London. His dad’s creativity literally infiltrated the house: much of the furniture, desks and cabinets were made by his dad. “He would get wood, knock them together, paint them all together, put it all together,” Skepta says. His family were different from others on the Meridian Estate. It was a melting pot representative of London’s increasing multiculturalism – there were white Irish, Indian, Jamaican and Somali families, but Skepta claims that the Adenugas were the only Nigerians there. Migrant Nigerian families typically settled more predominantly in south London – particularly Peckham, which is nicknamed “Little Lagos” – rather than north. But they also felt like outsiders in a more nebulous sense of feeling separate, which brought them closer to each other and meant that they assisted in enabling each other’s dreams. “So when we want to do something, we will just help each other, just do it and believe in it.”

The music culture of Tottenham propelled Skepta into his first opportunities in rapping and MCing. That evolution from rhythm junkie to full-fledged MC seems to track the history and development of grime too. Late-’90s UK garage was an incorporation of dance, jungle and R&B. It then begat grime, which emerged in east London and was derivative but distinct, with MCs spitting over “darker” garage instrumentals. This created a sound that thrived on pulsing basslines and trippy syncopation, that was explosive, raw, gritty and jagged. Rather than taking its cues from the sampling of classic tracks and instrumentals common in American hip hop, it was built with digital alchemy – expanding a practice of purely computerised production that had been revolutionised by Jamaican dancehall producers. Its peak is generally considered to be the early to mid 2000s, with artists like Wiley, the so-called “Godfather of grime,” Kano, D Double E and Skepta himself influencing its growth, as well as the crews and groups that emerged. Grime didn’t need the full force of studio production to find its footing; early grime artists created beats on the PlayStation game ‘Music 2000’, which allowed teenagers to skill themselves in production, sampling, mixing and mastering from the comfort of their bedrooms.

World-building was the marker of grime, as MCs spoke to the urban realities of life in London with its disputes, violence and aspirations for luxury which made it popular. A grime-fanatic friend of mine, Derrien, cites Dizzee Rascal’s 2003 album ‘Boy in da Corner’ as a classic example, with its tracks capturing the sonic atmosphere of the most deprived corners and sink estates of London – stairwells which smell of piss, basketball courts, trash strewn across the concrete, blinking lights, vibrant tag graffiti – and within that, hyped up and rebellious young men looking to channel their discontent.

As a schoolkid in the 1990s, Skepta started out listening to north London UK garage crew Heartless Crew and later became a fan of the crews Pay As U Go and Roll Deep, all early grime pioneers (he would eventually join Roll Deep alongside artists like Dizzee Rascal). It was only a matter of time before he ended up on pirate radio, where grime first arrived on the air waves, making his debut on Xtreme FM and Heat FM. “I made a little name on Xtreme but when I went on Heat, that’s when I became Skepta,” he says. Eventually, in 2005, he would form the collective Boy Better Know, or BBK, with brother JME as well as MCs Frisco, Jammer, Preditah, Shorty and Wiley. Many of these crews are now defunct, but BBK recently celebrated their 20th anniversary at Wireless Festival in London’s Finsbury Park.

Skepta’s parents were encouraging of his musical pursuits, though he laughs remembering that his mother used to drive him to his pirate radio sessions. “I wouldn’t have told her the radio station’s illegal. But she’s driving me there and the radio station is in some mad tower block – you’ve gotta climb through things to get to it; it was insane. She would drop me off down the road and sometimes I would walk the whole high road to get to the block.” The tower block was opposite a police station, which meant that it was often visited by bobbies (both Xtreme and Heat were frequently raided and eventually shut down by Ofcom).

This support for his music career was not without caveats that Skepta should strive to get a “real job.” His mother’s confidence in his prospects grew as she began to hear him on the radio, but there was still an undertone of needing a safety net in case the whole music thing didn’t work out. “Did they want you to go to university?” I ask.

“They wanted me to do all that Nigerian stuff, man,” Skepta says.

“Did you consider university?”

“Nah… I went to college for a short period, Tottenham College. It’s amazing that you said that, because that’s where I met the MCs that put me on to Xtreme FM. But when I went to college I was CORGI registered. I could do central heating. I could change the central heating in this whole building at one stage. I could drive a forklift – I had the licence and everything. I had a trade because my dad used to tell me, ‘You have to have a trade in this life,’ so I got a trade.”

“So if you weren’t a rapper and MC perhaps you would have been an electrician, or a forklift driver…”

“I’m handy, innit. I consider myself a handy kind of guy in any situation. Maybe a bit too handy… I love escape rooms. We do escape rooms all over the world wherever we go and I love figuring stuff out, helping the situation and being a team player!”

(RIVALRY)

But Skepta’s destiny was always to become the microphone champion, his involvement in grime clashes – where MCs battle to outdo their opponent with the most witty and damaging lyrics in a rapid-fire back-and-forth – quickly cementing his status as British rap’s MVP. Grime clashes are rooted in Jamaican dancehall clashes – unlike US rap battles, they both utilise “reloads” or “wheel-ups,” where a track is stopped and then played again from the beginning following a fierce response from the crowd. Where US rap battles are more a cappella, grime and dancehall are both structured by riding a “riddim,” a drum pattern with a sickening bassline, and if you spit bars with considerable flow then the crowd wills you to restart and go harder. Skepta’s interest in clashing grew from those Jamaican dancehall clashes – with deejays like Ninjaman, who went up against rivals Super Cat and Shabba Ranks. “Ninjaman is still my favourite clasher, my favourite battle rapper of all time.” Clashing had its roots on the playground too, cussing matches in school, with mocks of “pepper grains” (tightly coiled clumpy hair) and “ashy skin” and other anti-African jibes. His most high-profile early grime clash had been against Devilman, and it is still cited as one of the greatest clashes of all time. The lyrics are of their moment. But Skepta cleared his opponent with humorous bars like “Devilman can’t win lyrical beef / ’Cause he shitted in school and wiped his batty with a leaf.”

When Afrobeats star Wizkid’s second-to-last album, ‘More Love, Less Ego’, released in 2022, Skepta, who featured on the album and has three tracks with the star, wrote in a now deleted Instagram post that “when it wasn’t cool to be African in the UK I was screaming my Nigerian names from the rooftop.” This is a particular experience of millennial first- and second-generation African migrants; the cultural “cool” of being Nigerian would not materialise until the explosion of Afrobeats music in the 2010s, and when Skepta was at school it would’ve been “cooler” to be of Caribbean descent. Responding to this on producer Plastician’s 2007 track ‘Intensive Snare’, he raps, “I’m a bad boy from Nigeria, not St. Lucia.”

I wonder how anti-Nigerian sentiment might have thus shaped Skepta’s early experiences. “I’m from early multicultural England. My dad obviously faced this earlier than me. He used to tell me stories of when he used to DJ and skinheads used to come in the club looking for black guys. But then I experienced a different version of it, where in school everyone’s calling each other names. Which is kind of cool because it builds you up, you’ve got tough skin, you’ve heard everything.” He used his short film, ‘Tribal Mark’, to reflect on some of these pejoratives around Nigerian identity and embrace them as a “superpower.” “When you’re older, you realise people now go on to ancestry.com to find out where they’re from… When I was younger I was getting teased for knowing where I’m from. So you grow up and you learn to love it all, man.”

He first visited Nigeria when he was 17 years old. “I was kind of pissed off that my whole school time I’d been lied to. Like they used to say stuff about Nigeria, like, ‘You lot eat this, you lot do this, you lot smell like this,’ and I got there and I was, like, “This place is amazing.’” When he returned to the UK he knew that when he got on the microphone he was “gonna be this heavy African Fela Kuti rebel-type rapper.”

(SEXY UGLY)

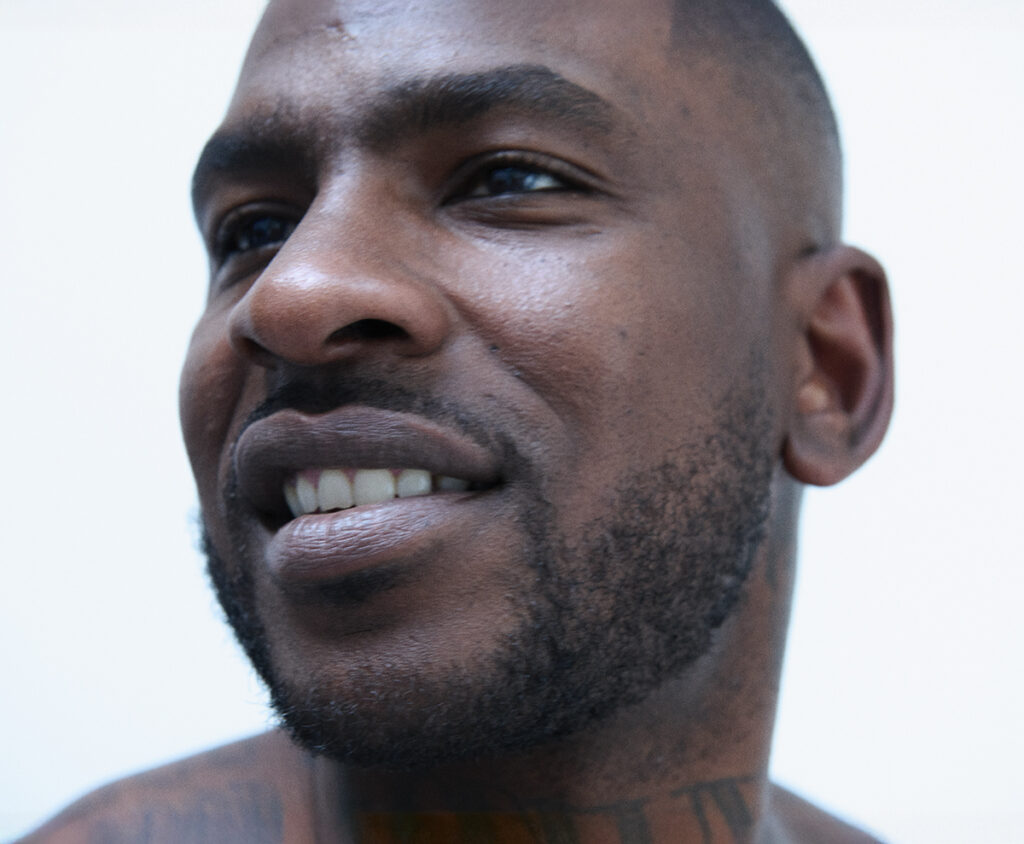

Skepta is surely one of the most beautiful men in the UK. I can’t properly describe how perfect his face is in person: he has bedroom eyes and a lovely, gorgeous smile, but he looks dominant. It feels awkward to ask someone about their own beauty; does he see all the thirst posts about him across social media? “I find it funny,” he says, but he is visibly disinterested in dwelling too much on his own appearance, in fact turning from me and looking at his feet as if shy.

“Does being regarded as a beautiful man do anything for you, emotionally? Do you feel a sense of pride or confidence from it?”

“Not really. If I was to believe it then I’d believe the bad things that people say about me online, too. I don’t really get into that, because I feel that my strength and a lot of my power comes from ugly. I walk around with a stank face, because I feel like I represent that. I represent ugly. Even in my first lyrics I used to say, ‘Joseph Junior Adenuga. Big lips, African hooter.’ That’s my energy.”

He speaks with such burning passion – it begins to sound like a manifesto for political ugliness.

“I want the people who ain’t the conventional, whatever beauty is, to feel, like, ‘Okay cool, I’m gonna listen to Skepta. If Skepta’s saying he’s got rubber lips, dry elbows, pepper grains…’ bare stuff that I used to get called in school. And it’s, like, now I got time to drink water and buy nice stuff and get a haircut and people are, like, ‘Yeah, Skepta, you’re bare nice’ I’m, like, ‘Okay, thanks, cool. But I’m not about to let you lot trick me out of my position to make me feel like a sweet boy when I got here with the resilience and the rebelliousness of being ugly and not being part of the crowd.’”

I feel strangely emotional hearing this. I’m 15 years younger than Skepta, but I was called some of these things in school, too. I feel strangely disarmed and vulnerable, so I tell him that I’ve felt ugly at times.

“Yeah, but you’re a good-looking guy. You are! But you probably wouldn’t have been if you didn’t feel like you had to get out of that headspace of what I’m talking about, or you didn’t feel the rebelliousness of people saying all this shit. So for you to start getting into it too much now, I feel like you’d just lose your swag.”

I don’t think about it until after I’ve left him, but I wonder if Skepta would enjoy reading Virginie Despentes’s ‘King Kong Theory’. Despentes writes from the position of “ugly” women, who are “more King Kong than Kate Moss,” and uses that to build a challenge to societal norms and structures of power. Of course, it’s a feminist text written by a white woman, far away from the reality of Skepta and myself as Black, African men, yet there is something foundational there about conceptions of beauty and outsider status that also resonate in Skepta’s words.

(DADDY)

Skepta is significantly more thoughtful than you’d imagine of a man who went viral for a clip from a 2018 ‘GQ’ interview alongside Naomi Campbell where he stuck his fingers in his ears at the mention of politics. (He says he resented that moment but now enjoys the memes.) So I ask him how he has felt the change from being a scrappy, clashing young buck of the grime scene to a senior cultural figure in Black British and broader urban culture. He’s certainly embracing of younger artists, whether it’s premiering a new track, ‘Sirens (From Ireland)’, with up-and-coming rapper Finessekid or collaborating with impossibly talented and punkish British rapper Lancey Foux. “For me there’s this flow that’s happening where young artists somehow end up around me and they have stars in their eyes. And I’ve realised where young people with that twinkle in their eyes get tricked out of their position by labels. There’s lots of different ways for them to get effed over. So for me, I always try and show them that they’re gonna be good. This music thing’s a journey. There isn’t a Grammy or a Brit or an award you’re gonna win that you’re gonna hold up and say, ‘I’ve done it.’ There isn’t a ‘done it.’”

He’s aware, though, that the possibilities of building a career and getting your start in rap are rigged in today’s cultural landscape. Black British music in particular is struggling – DJ and writer Elijah wrote in ‘The Guardian’ in 2024 that radio stations are ignoring Black British artists to “play recycled American rap.” Skepta’s take on this is that it is linked to the decline of clubbing and raving culture.

“Within every movie – whether it’s ‘Paid in Full’ or ‘The Godfather’ or ‘Scarface’ – is a community; they have a club. The club is a hub for the fashion, the music, the slang. This is where everything gets born. I feel like we had that with Visions nightclub in east London – it was the best that the UK has ever seen.” Visions Video Bar in Dalston was a much-loved nightclub and staple of the Black British partying scene. It closed down suddenly and without warning in 2018, though the venue reopened in 2024 under the name Sui Generis. Visions was the kind of place that was a haven for up-and-coming artists but that could also command the attention of high-powered American acts like Pharrell and A$AP Rocky, who would turn up despite the space being “a hole in the wall, the width of an ATM machine.”

Skepta continues, “Since we lost clubs like that, I feel it’s harder for artists. I come from a time where we had loads of clubs to go to. I could go to Leicester, then Stevenage, then back to London in one night. But now, what do you do? You make a song and you have to go and do a TikTok. It’s a crazy hard time in the UK right now.”

Skepta is aware of how what was once an open and democratic raving culture is increasingly being cannibalised by brands, because of issues of funding and access, leaving these spaces more exclusive and invite-only. He further fears that young artists are often “just sitting around waiting for Wingstop to ask them to pop up at some exclusive collaboration that they’re doing with whoever,” and he concedes that “when the scene and city is just left to that, then I think it’s over, personally.” He imagines resurrecting London’s cultural and social infrastructure on a more grassroots basis: cultural hubs, youth clubs, spaces for people from all ages, from school children to pensioners. “Otherwise we’re just left to the rule and control of these elite, exclusive events and that facade.”

Could helping to revive London’s rave scene, and opening up those avenues for new artists, be something he wants to leave for the next generation? Sure, but not for the reason of legacy. It’s not a concept he’s especially interested in, as someone who doesn’t really “think about anything from before… I don’t even know where my awards and plaques are.” He is so incredibly present that what’s most immediate to him is what’s most important. The past is only that. “It’s all preparation for now, for talking to you, innit?” he says. “It’s like if I hear a beat and I want to go in the booth and vocal it, I’m not going in the booth as Skepta or nothing like that; I’m just gonna go in the booth as today. How I feel today, what would be a great song today, from an artist that nobody heard of ever in their life.”

(FRIDAY 11PM! SATURDAY 9PM?)

A few days later, on Friday at the Glade stage at Glastonbury, Skepta is there with his DJ collaborators, comfortably grooving, with his tracks ‘Victory Lap’ and ‘Cops & Robbers’ taking off alongside mixes of Ciara’s ‘Goodies’ and Missy Elliott’s ‘Work It’. Any sense of the panic that consumed him when I mentioned the set at his studio earlier in the week has vanished. It’s as though he was always meant to be here.

Curiously, the sole image being projected is of a dove extending its wings, like a symbol in a propaganda video. Skepta is in a hoodie wearing a beanie with tassels, which make it somewhat resemble a tarboosh.

As I’m in the crowd watching him I reflect on the fact that this man likely has no idea where he is meant to be tomorrow. The day will present something new and that is what he will get on with.

Remarkably, on Saturday, the universe really does deliver something unexpected. And Skepta is ready to greet it. The phenomenon of surprise sets at Glastonbury has long gone the way of “secret menu items” in fast food restaurants – supposedly secret but now so widely circulated and shared that they have become little more than a marketing exercise. All week there have been leaks and rumours of surprise sets by Lorde, Lewis Capaldi, Pulp and Haim, so that when they do arrive it feels totally expected. Any claim to actual spontaneity is truly dead.

But when the band Deftones pull out of their performance on the Other stage (the second largest at the festival) due to illness and Skepta steps in with only a few hours’ notice, it feels like a genuine shock.

In a statement, he says, “Let’s go!!! No crew, no production but am ready to shut Glastonbury down. Victory lap time. Pre-Big Smoke 2025!” To me, it simply confirms that sense that he rarely thinks beyond that which is immediately in front of him. If that happens to be a huge stage at the largest music festival in the world, so be it. He’s there and ready. When he steps out, he is wearing a durag, rimless glasses and a T-shirt on which his clown-make-up painted face from the music video of BBK’s 2009 smash hit ‘Too Many Man’ is printed. There are young girls at the front rail who’ve staked out a spot for Charli xcx later that day looking a little confused, but most of the crowd is leaping around, gun fingers in the air, hands clasped over their mouths, skank ready. What unfolds is a sonic feast from grime’s MVP: a shutdown, frenetic performance which runs the gamut of his discography. For Skepta, I suppose it’s just what he felt like doing that day.

Photographic assistance by Bella Sporle, Thomas Lombard, Daiki Tajima and Andrew Edwards. Styling assistance by Anna Sweasey and Lucy Proctor. Tailoring by Della George. Grooming by T-Styles. Make-up by Shanice Croasdaile. Set design by Andy Tomlinson at Streeters. Post-production by ALY Studio. Production by Partner Films. Special thanks to Dream Cars.