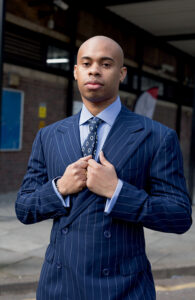

Shayne Oliver

At 28, Shayne Oliver, the founder of Hood By Air, is the most disruptive designer in American fashion

Ten years after vogueing onto New York’s fashion scene with his brand Hood By Air, Shayne Oliver has successfully thrown the gravitational centre of American design off its axis. His work uses its foundations in streetwear and the club scene to present something pioneering and progressive that explodes staid notions of luxury and high fashion. Having built a loyal fan base of young customers who feel an inherent connection to his work, Shayne is now commanding the attention of the fashion establishment, winning the LVMH Special Prize in 2014 and the award for menswear at the 2015 CFDAs. It is no exaggeration to say that the success and freshness of Hood By Air’s aesthetic have struck panic into the core of parts of that same establishment, spawning a steady stream of imitators frantically trying to predict what will come next. Shayne, though, remains steady, at the centre of the ever-evolving coterie of friends, collaborators and supporters who make up the universe of Hood By Air and represent his refreshing, familial and social approach to doing business. In New York, his home is a second-floor bedroom in his mother’s Prospect Heights house, but he is currently in Paris, setting up camp in an informal studio in the city’s 8th arrondissement, from which he looks back across the Atlantic, contemplating his next move.

From Fantastic Man n° 23 — 2016

Text by BIJAN STEPHEN

Photography by WOLFGANG TILLMANS

Styling by CARLOS NAZARIO

At 2 in the morning, Shayne Oliver looks more vivacious than anyone else in his tastefully appointed Airbnb in Paris’ 9th arrondissement. Vera’s ‘Take Me to the Bridge’ is blaring out of the living room speakers; drinks are everywhere, some fresh, some playing host to discarded cigarette butts; and Oliver is vibrant, in his element. He’s presiding over the party, checking in on his friends and flitting between conversations in the particular way that good hosts do. The crowd skews very young, mostly between 18 and 27, and all those assembled (models, friends, assorted affiliates) reflect Shayne’s taste in people. Which is to say: they’re all intense, accomplished and beautiful. In his designs, it’s much the same – through the clothes he makes, Shayne is creating the culture he wants to see in the world.

But let’s back up. It’s raining in Paris the week that I meet Shayne, the 28-year-old grande dame of Hood By Air, the haute streetwear brand that he founded when he was 18. In the last few years he’s picked up awards – a CFDA award, the prestigious LVMH Special Prize – a dedicated cult following, and celebrity devotees.

When he shows up to meet me at the L’Avenue restaurant on Avenue Montaigne a few minutes after the appointed hour, he’s trailed by Walter, a good friend and casting director for the label, and Morgane, HBA’s publicist. Shayne is wearing over-the-knee stiletto-heeled boots, a trench coat he appropriated from his Airbnb, and a padlocked chain around his neck, which he later tells me has been there for two years. (“I haven’t been bored enough to cut it off,” he says.) Walter has on a full-length black HBA fur and a complicated white sweatshirt constructed entirely from zippers. Together they make a striking pair. (Morgane, on the other hand, looks flawless in a conservative Parisian way, which is to say less like the HBA kids than like the rest of the people in the restaurant.) I joke that our setting – a grand restaurant dripping with wealthy Parisians and located on one of the most expensive pieces of real estate in the city – must mean that he’s made it, but he doesn’t laugh. He doesn’t think he has. “Maybe that’s my problem. I never really feel like it.”

Our meeting takes place a few days after Shayne showed Hood By Air’s most recent women’s ready-to-wear collection in New York and about a month after his most recent menswear presentation in Paris – though Hood By Air has done more than maybe any other current brand to render the division between male and female fashion obsolete. The ready-to-wear show featured a half-naked, muscle-bound Slava Mogutin, the exiled Russian activist, writer and artist, striding the catwalk holding a patent puffa jacket-life-raft-hybrid above his head. The men’s was held in a concrete bunker in the Marais, where some street-cast models stomped and careened around while others lay on their backs on old mattresses, legs in the air, strapped into shoes bolted onto wooden planks that hung on ropes from the ceiling, loaded with burning candles. It was perfectly timed, presented on the one day that the menswear and couture fashion-week schedules cross over. “I think we’re ready for a men’s couture moment,” Shayne said at the time.

Now Shayne, in Paris for sales and showrooms, is in the mood to reflect. “I looked at the show today, and this is the first time I’ve ever looked at a show, like, one, two days after,” he says. “I usually wait, like, a month to actually look. I listen to what everyone is saying, and then I look, and then I make my own decisions. I think a lot of what I do is a commentary on the state of fashion at the moment.”

Hood By Air is a commentary on the state of fashion, sure, but HBA is also a scintillating disruption of fashion’s established order. Since the brand’s chaotic beginnings showing in NYC nightclubs in the mid ’00s, Shayne has used it as a vehicle to elevate and develop street and club aesthetics into high fashion and to challenge the staid, exclusive old-fashion status quo. No brand has been more instrumental in making the fashion industry sit up and pay attention to its endemic problems with diversity and representation. Simply by presenting a new aesthetic – in shows peppered with his wonderful cabal of friends, collaborators and associates of all kinds of ethnicities and gender variations – Shayne has thrown a challenge to the industry. To put it plainly, what he does makes everything else look outrageously conservative and mind-numbingly dull. I want to know what it’s like to be inside the disruption. To challenge the establishment is no easy thing.

“You have a very diverse clique, it seems like,” I say to him. “How do you think that goes over in the fashion world?”

“It doesn’t go over so well!” Shayne replies. “I mean…it’s a lot of personality. I do think that everyone is respected. I actually don’t know, to be honest.” He goes on: “I more so get reports from the kids about how they’re being treated, and they know not to tell me certain things.” I can only speculate on what that means, but from the way Shayne says it, the “certain things” seem to be casually bigoted remarks. It doesn’t seem to faze him at all; he’s much too concerned with his work to let anything like that get in his way.

At the end of our first bottle of wine, two of Shayne and Walt’s friends make their way into the restaurant – first Delphine, who’s a magazine editor, and then Alex, a model. Shayne, Walter, Delphine and Alex all speak in code, in the shared language of people who have spent a lot of time together. As far as I can tell, they refer to what we’ll do later in Shayne’s apartment – party – as “chopped”, having a “ki”. Everyone mentioned is referred to on a first-name basis only, as if everyone is famous, though I have no idea who anyone is talking about. Walt and Shayne high-five every time either brings up one of their numerous accomplishments, providing a constant, staccato accompaniment to the Chablis and meandering chatter.

According to Morgane, we’re needed down the street at the LVMH Prize semi-finalists’ showroom at 7pm. We leave after 7.30. “I’m feeling a little Liza Minnelli,” Shayne says before we go; I take it to mean that he intends to make a scene.

Shayne Oliver was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to a Trinidadian mother who was a teacher. Until he was 10 years old, he split his time between there and his grandmother’s place in Trinidad. After they moved to New York City, they lived in Brooklyn’s East New York neighbourhood before moving to Bedford-Stuyvesant. Today Shayne’s mother lives in Prospect Heights, a quiet community resting against the edge of Brooklyn’s famous Prospect Park. “While I’m in New York, I actually still stay at her place,” Shayne tells me. It’s a cute way to say that he’s yet to fly the nest. “I move around so much that I don’t really have my own, like, place.” Shayne is swarthy, medium-height and barrel-chested, with a snipped right earlobe. On his physique, Hood By Air’s clothes fit like they’re supposed to, and the aesthetic combination of a stocky man wearing genderfucked clothing is instantly arresting. It was conceived in 2006, a full decade ago, as a menswear brand, but Hood By Air’s boundary between masculine and feminine has always been blurred. Since he started to show on the men’s schedule in Paris as well as in New York, Shayne tells me, he’s been bringing the label even further around to femininity and explicitly feminine looks. “As I get older, I connect more with women,” he says. “And I want to do more things that are womenswear-based as I start to like it. I think that the designs I was playing around with at the start of Hood By Air were relevant to me because they reflected what I was around at the time. And now I see these women and how they’re really influential, and I see the power of basing design on that. I want to see what it feels like.”

As our conversation wends on and Shayne gets more expressive and discursive, I begin to get the sense that his design influences well up from a deeply personal place. Take, for example, his enduring love of vogueing, which somehow finds its way into most of his presentations. “I’ve been a dancer forever, and I think that that is emotive,” he says. “It’s like the person is communicating the idea through their body.” It’s a form of communication he began using when he was, in his words, still in “straight high school” – Robert F. Wagner, in the New York borough of Queens – and a gay teacher told him to go to an after-school programme for gay youth in Manhattan.

“We would have a little snack, maybe smoke a little weed, and then just vogue for hours and hours and hours,” Shayne says. “I actually had my moment there, for the first time. At school, in the straight world, I was constantly being super mature, holding the status quo up. Once I got to the programme, I totally felt like I could laugh with people and be messy with people. I could do that thing everyone else, like straight people, could do every day in high school. Us hanging together was like gym class was for jocks. It was a place where we could be how we wanted to be.” Before the end of high school, he transferred to Harvey Milk High School in the East Village; the school was designed specifically as a safe space for LGBT students.

After a brief, failed stint at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York – “I just kind of felt like I didn’t fit in” – Shayne began designing clothes for himself and his friends to wear to the club. He taught himself as he went. The first T-shirt came out in 2006, and other pieces soon followed. Shayne collaborated in the early days with Raul Lopez, making samples with Dominican tailors Lopez knew on the Lower East Side. (Raul left the brand in 2011 and moved back to his native Dominican Republic to start the label Luar Zepol.) In October of 2007, after a couple of nightclub shows, Hood By Air sold its first collection to a New York City store, and by 2008 the brand had begun to gather stockists in Europe as well as the US. “A lot of that early work was based on things we’d be wanting to come to pass, or things we imagined and wanted but that had not existed, that weren’t available for us to buy, or at least look at in person. It was about knowing exactly what I wanted to make.”

Akeem Smith, a stylist and a close friend who eventually became HBA’s art and image director, met Shayne in 2008. They became fast friends, starting up a routine of going to male strip clubs every Monday. As the person responsible for styling the brand’s shows and presentations, Smith was one of those who helped to create Hood By Air’s distinctive style; on the phone with me, he describes it alternately as “third-world” and “alien.”

In 2009, the musician Venus X – one of Shayne’s close friends, collaborators and muses – founded a monthly party series called GHE20G0TH1K, which drew everyone from New York’s underground scene. For the next three years, Shayne DJ’ed as ShayneHBA and helped to host the party along with Daniel Fisher. “I was never formally a DJ, so it was very harsh,” he said of his style behind the decks. It was, of course, another extension of the brand and served to bolster its sense of community and commitment. Shayne surrounds himself with his people, as Andy Warhol did at his Factory. The parties influence the clothes influence the music influences the parties influence the clothes.

In 2013, Hood By Air had its first New York fashion week show, at Manhattan’s Milk Studios. “By the time that show came around, the brand was already really well known,” Shayne says. “We had a few good stockists, but not many. As far as business was concerned, the way we were doing everything was just intuitive.”

The wider fashion world had taken notice by then, and HBA copycats were everywhere. “There are few contemporary brands as relentlessly knocked off, copied, and versioned,” the Business of Fashion website wrote in 2014. Even so, Smith says that he and Shayne didn’t feel that HBA had made it into the “big leagues” until last year’s ‘Daddy’ show for Autumn and Winter 2015. “The show was life-changing, because Shayne and I realised, ‘This is sort of it,’” Smith told me.

The vibe of that show was stark and kinetic, with a pounding electronic soundtrack (mixed live by Total Freedom) that segued into a smooth Duke Ellington jazz groove after a quote from Taraji P. Henson’s character on ‘Empire’: “I wanna show you a faggot really can run this company.” The audience was rapt. It’s common for fashion brands and houses to bring in DJs or musicians for their presentations to buy in a bit of club culture and give themselves some youth credibility, but it’s very rare for the designers to have the deep, authentic connection to the sounds and the scene that Shayne does. At his shows, editors are exposed to something entirely new to them, straight from the source.

“I was magnetically drawn to him,” said Alejandra Ghersi, aka Arca, the musician and producer, who has collaborated with Shayne for Hood By Air show soundtracks; she’s also worked on records by Kanye West, Björk and FKA Twigs and made two sensational albums and several EPs of her own. Alejandra, then a student at NYU, met Shayne at GHE20G0TH1K. She offered to be Shayne’s intern, and they quickly started making music together, recording an album in 2012 and ’13 that they are releasing now, under the group name Wench. “Through making music we got to know each other quicker than anything else,” Alejandra told me. “I can tell you, it’s always, always been so much fun. Meeting Shayne is a catalyst for looking into yourself and seeing how many layers you can shed to be comfortable with yourself.” I said that Shayne seemed to be a new Warhol, at the centre of his own creative solar system. “I like Shayne’s work more than Andy Warhol’s,” Alejandra replied.

In Paris, Shayne, Morgane, Walt, Delphine, Alex and I finally make it to LVMH, and it’s manic. Outside, smoking a fortifying cigarette, Shayne tells me he’s nervous.

Two years ago, in the inaugural year of the LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers, he won a special prize of €100,000 and a yearlong mentorship here. He’s grown a lot since winning. He’s all business when we walk into the showroom, and his attitude telegraphs the kind of haughtiness that comes with knowing intimately the ins and outs of the business industry. He’s not on autopilot, not quite, but he knows how to play – and win – the game.

It’s impressive to watch him at work, weaving amongst a crowd that, compared to him, moves somewhat clumsily, their agendas on full display. While I’m ducking out of pictures – there are photographers everywhere – Shayne can’t go five feet without someone asking to take a photo with him or stopping him for a chat. The crowd is restless, bored and hungry. They’re hungry in that vampiric, young-blood-loving way, restless in their constant search for more important people to talk to, and above all, bored, in that peculiarly fashion way. Alex and I trail behind Shayne, Walt and Delphine, who all have their own people to see.

The 23 semi-finalists for the prize have booths in the showroom, and Shayne visits all but one. He’s particularly impressed with London menswear designer Grace Wales Bonner, who’s got a magnificent set-up and a beautiful, onyx-skinned model. Earlier, I’d asked Shayne which designers he admired most. “Alaïa,” he said immediately. “At the very moment…” he paused. “Phoebe (Philo, of Céline) is always on for me. Rei (Kawakubo, of Comme des Garçons) – Rei is always good. I feel like HBA has been playing around with this idea of fuck this thing,” he continued. “I think that I find pride in young designers, people that do cool stuff, like now. People who are pushing boundaries.”

We’re there for 40 minutes, maybe, but it feels like forever; everyone is moving so slowly, and the constant camera flashes are exhausting. Alex and I slip away to the Plaza Athénée, where I buy a pack of Marlboro reds from the concierge. Alex is 18, I learn, and has only known Walt for four months. In that time, according to Walt, she’s apparently become something of a muse for HBA. I can see why. She’s tall, thin and arrestingly beautiful, especially when the light hits her cheekbones the right way. She’s been modelling for two years and is Estonian; she’d walked for Maison Margiela that day and has walked for everyone else too. On the side, she’s beginning to work as a video artist.

After a short Uber ride back to his Airbnb, Shayne is determined to have a party. He’s thrilling to watch. He FaceTimes aggressively. People start showing up. It’s an instant ki. After a few hours, everything’s in full swing. There are so many twenty-somethings in the room that it feels like spring. Everyone’s happy, everyone’s shining, everyone’s blooming. The people Shayne surrounds himself with are fiercely loyal and seem inexorably drawn to him. He has founded an entire creative world that’s an extension of his personality, like the clothes and the music and the parties.

This, more than anything, demonstrates that HBA is an expression of a community, a lifestyle. Shayne works in fashion because it’s his most comfortable mode of self-expression, but it’s the shared attitudes of this community that shape it. The brand is social, with a peculiarly collective way of working: everyone moves seamlessly from nightlife to business hours and back again, and everyone collaborates on ideas and how to execute them. They actively negate the appropriation of their work and culture. If something of theirs gets too big, they abandon the idea or transform it into something unrecognisable.

If this is HBA’s heart – transgression as ethos, as progress – then it reflects both the soul of youth culture and this community’s own identities: young, queer, of colour. It’s in those identities crashing together in the service of ideas about what fashion can be that HBA has taken shape. I won’t purport to know Shayne’s heart, but I can tell you about his instincts – because they’re right there in the clothes, the employees, the models and the friends.

At the party, Shayne is preoccupied with delight. But I want to ask again the question that I tiptoed around at the restaurant. I want to know what it’s like to be black in the fashion world, which is so notoriously and problematically white. I want to know how he feels. I think I can identify with how he might feel – we both work creatively, and we share an Afro-Caribbean heritage and similarly dark skin. This time, in his apartment, I don’t bother with formality. What’s it like? I ask. Shayne sighs, pauses and then tells me this: he doesn’t want to be representative of all the black people in fashion. He doesn’t want to be this kind of token, even as he’s aware that many people do, in fact, perceive him that way. He doesn’t want to have to represent anyone but himself. It’s not because he’s black that he’s in the rooms he’s in. He’s right. Shayne Oliver is invited into certain rarified rooms because he has good ideas. He shouldn’t have to worry about representing anyone but himself, or be anyone but himself. He has lost the key to the lock that hangs around his neck, but he is in control.

The next day, I wake up early in the afternoon, jet-lagged and terribly hung-over. I text Shayne, and we agree to meet that evening at the showroom so he can give me a tour of the new collection.

Hood By Air’s new temporary Parisian head-quarters are spare and hidden behind an apartment complex’s robin’s-egg-blue set of double doors. In the courtyard, there are plastic folding tables and chairs emblazoned with the black, block-lettered HBA logo, which in the last 24 hours I’ve grown used to seeing everywhere. Shayne meets me at the door and escorts me inside.

In the corner of the room, people are quietly working. Shayne looks a bit tired from last night’s exertions, but I can tell he’s focused. Chill music filters tinnily out of laptop speakers – the crew has gotten very into coldwave – but the clothing is the loudest thing in the room.

The collection, neatly hung on racks that take up half the room, is a conflagration of patent leather, fur, zippers and vinyl; each piece is immaculately textured, from the fur made from 14 silver foxes to the knee-length coat made of glossy leather and chromed zippers. It’s sinewy work – a little leather-daddy – and it feels like a mature aesthetic compared with collections from a year or two ago.

Shayne gives me the tour, pointing out past catwalk pieces and new retail ones. He explains that several of the more outré runway items will now be finding their way to stores – something that had proved difficult to pull off in the past – because the brand has begun to work directly with factories rather than rely on a production agency.

Shayne tells me he’s been particularly focusing on fabrics recently – before, he really only concerned himself with shapes – and the result is stunning and fittingly ambitious. The sense of progression, of controlled and considered growth, prompts me to ask where he sees Hood By Air going. Can the party continue forever? Or does Hood By Air need to change its approach so that the brand can keep growing? “I want to make a very healthy, very strong house that is well off and supports everyone and makes everyone that is working in the company well off,” he says. “The idea of Hood By Air is not to take over every corner of every market excessively, though, so maybe I would do another project. As a designer, there may be other things I want to do.”

It seems obvious, given the success of Hood By Air and the speed with which the fashion establishment now moves to pick up the next big thing, that Shayne must be being courted by major conglomerates and brands. He hems and haws and stutters and deflects when I ask, until finally he settles on “yes.” He won’t say any more. I suspect it’s because he’s looking for the right fit and doesn’t want to dissuade any comers, but he does add that his main objective right now is to make sure HBA stands alone, regardless of external support or accolades. “I just want to have a great structure here,” he says. “I want to continue developing this great structure where we’re unbothered and we can interact with other people, other companies, but we’re not banging at the doors of other companies to be supportive, or whatever.” It’s a noble goal. Hanging around the showroom, I can tell that everyone involved is totally committed to it, and to Shayne and his vision: they work with the conviction of people who know they’re doing the right thing.

The sun is setting when I leave the showroom, and it’s a brilliant sight. The city is coming alive for the night. I don’t know what time Shayne leaves the office, or what will come next for him tonight or in the coming months, but I do know that he – like everyone else in the city – will eventually emerge to taste the air. He might ki, he might make a scene, he may not sleep, but whatever he does, he’ll do it with conviction.

Photographic assistance by Simon Nicholas Gray and Annett Kottek. Styling assistance by Giovanni Beda. Hair by Alex Brownsell at Streeters using Oribe Haircare. Make-up by Nami Yoshida at D+V Management.